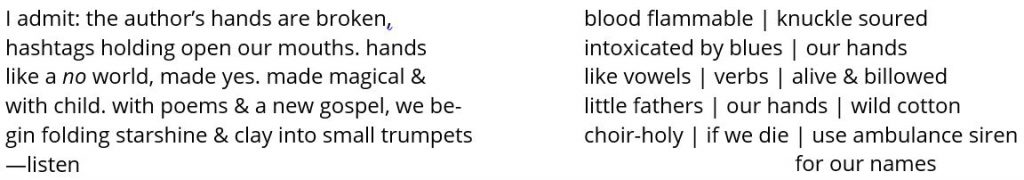

Aurielle Marie:

Interview + 4 Poems + Audio

Aurielle Marie is a Black and Queer poet, essayist, and cultural strategist. They are the author of Gumbo Ya Ya and the winner of the 2020 Cave Canem Poetry Prize. She is a child of the deep south and the Black griot tradition. A genderqueer storyteller and community organizer, Aurielle writes about sex, bodies, state violence, and the south from a Black feminist lens.

Aurielle’s poetry has been featured or is forthcoming in TriQuarterly, Southeast Review, Black Warrior Review, BOAAT Journal, Sycamore Review, The Adroit Journal, Vinyl Poetry, Palette Poetry, and Ploughshares. She’s received invitations to fellowships from Lambda Literary, VONA Voices, and Tin House. Aurielle is a 2017 winner of the Blue Mesa Review poetry award. She’s the Lambda Literary 2019 Poetry Emerging Writer-in-Residence. She won the 2019 Ploughshares Emerging Writer’s Award for Poetry. Aurielle’s poetry debut, Gumbo Ya Ya is the 2020 winner of the Cave Canem Poetry Prize, and is out from the University of Pittsburgh Press.

As an essayist, Aurielle explores subjects of justice, Blackness, bodies, sex, and pop culture in an urgent and lyrical voice, from a Black feminist lens. She has bylines in The Guardian, Bitch Media, Allure Magazine, Essence, Wear Your Voice, NBC, and Teen Vogue. They currently serve in the 2021 cohort of Press On Media’s Freedomways Reporting Residency and are in a creative curatorial stewardship with Lead to Life through 2022.

Photo by Keyonna Calloway

INTERVIEW WITH AURIELLE MARIE

Questions by Brittany Rogers

Editor’s note: It was a pleasure to interview Aurielle Marie for this issue of Revolute. Aurielle is brilliant, thoughtful, and delightfully hilarious. In between lots of laughs and discourse, we managed to carve out an interview. I stick as true to the original conversation as possible, but you should know that you are getting a version of this discussion that has been abridged for time and clarity’s sake.

Brittany: [Recently] I was listening to a talk that Kiese Laymon did with Tressie [McMillan Cottom] on revision. During the talk, he discussed the notion that Black folks especially are discouraged from the idea of things shifting or changing—that once we say something it is set in stone, and it could never be touched or played with. And I was like, you know, who doesn’t mess with that as a construct? Aurielle!

Aurielle: Cuz it’s gone change.

Brittany: And looking through your book, and your revision of gospel and the way we think about religion, or the way we think about family, or language, or even playing around with “Acknowledgments” and “Notes” [in Gumbo Yaya]—would you mind talking about your relationship to revision?

Aurielle: I think I was where Kiese was describing for a while because I thought that in order for the poem to be done you had to be sure . . . and your certainty creates the period at the end of the sentence. And that was unsettling for me, even at the time. I was someone who would go back to a poem I had written four years ago and change it into an entirely new poem. I [would] pick up a poem from when I was slamming in high school and look at it like, Oh what are we doing here? These three lines are cute. The structure is cute. Let’s change it into a new thing. I just thought that that was like cheating because here is this poem that’s been done, it’s been on the stage, and now I’m trying to go back and make it a page poem.

Brittany: Interesting!

Aurielle: [Then] I was in a workshop with Danez [Smith] at VONA [Voices of Our Nations Arts Foundation]. And I felt like I was cranking out fire poem after fire poem. One poem was called “Hashtags,” and I didn’t understand why it wasn’t landing at workshop. I just thought it was the most amazing poem I had ever written; I was so in love with it. It even made it into the manuscript for the book that won the Write Bloody [Jack McCarthy Book] Prize, and Danez was like it’s good, but I don’t think this is the last poem in the book. And so I went back to the poem, and I thought to throw it into a form to see what could be squeezed out of it; that poem became “Pantoum for Aiyana.”

It brought its old life with it, and it became the thing it was supposed to be, and I realized that I was so drawn to the poem because somebody in me knew where it was going to land. So then I took this entire book that was going to have its own life with Write Bloody, and I pretty much edited every single poem into its own form just to see where it was off. This was also in a time where I hated form (because the way it’s taught is ew) and I was using form as a sort of kiln to get to something else on the other side, even if what came out on the other side wasn’t the final product. It became really useful for me to show the reader the revision side of things by naming the choices that I found myself stuck at.

If I found myself stuck at a choice (like do I cut this line, do I use this word or that word), I would try putting that in the poem for the next version. So, for example, the poem may say a former version of this poem could have stopped here, but I have more to say (on my Ross Gay). The ending of the poem is just what feels most necessary right now, and that gives me permission to change my mind at any point in the process. And now I’m going all over the place. Like, how do I feel about revision?

Brittany: There is something very resonant in the way that you’re talking about revision as just a time, as opposed to a destination. I often think that revision is where I’m stronger as a writer, but I do think I was taught that there is a complete version of a thing, and that has limited my imagination.

Aurielle: For me that’s the scariest part: that there is a hard end point, and you have to write or revise your way to that hard stop, and you can overshoot it or undershoot it or just miss it. That terrifies me honestly, so I just think of myself as having unending access to the poem and the poem has unending access to me. My revision journey is just learning the poem and allowing the poem to impact me and having a relationship with it until I feel satisfied. Like this whole book was a result of me looking at my old poems and just continually editing them until they’re whole new bitches. I have a life with the thing that is changing me as I change it.

Brittany: So this ongoing process—I don’t even wanna say erasure because that doesn’t feel accurate.

Aurielle: I think that’s a thing about this book that I’m really satisfied with. None of the poems feel stagnant. Like going back to read it, I almost feel like page 31 or page 52 is doing something before and after I open it—like, very much on its Toy Story shit! It has its own little life, and then there’s the moment that I read it, and then I leave it, and it has its moment where it goes back to OK girl, and I think my revision process is just trying to get to the point where I feel satisfied with where we meet one another.

Brittany: I love the Toy Story analogy! Something that I felt so deeply was how each poem felt like it was bringing the speaker, but it was also bringing in a gang of folks. For example, when I’m reading “’I, too’ sing America,” of course I’m thinking of Langston Hughes, but now I’m thinking of Danez Smith, and then you cite [the poet and rapper] Noname . . .

Aurielle: And Diamond Forde, too.

Brittany: Ah yes! Throughout your book, I felt like I was either re-meeting old friends or meeting new friends. Lineage was such a clear foundation and focus, and I would love for you to speak to the importance of that for you.

Aurielle: When I was younger I wanted to write a book, but the reason I didn’t set out to be a 15-year-old published author was because I couldn’t figure out how to get the page read of a poem to feel like the slam space [I grew up in], where you are not just with your team, but with the team, the audience, and then the team’s crew. If you’re around long enough, you start to recognize the teams, and this person’s brother, and who comes out to cheer for who, and the entire network, and it adds to the context of what’s happening on the stage. It’s alive and I felt like I couldn’t recreate that, and if I couldn’t recreate that then [writing] was boring.

So when I revisited the idea of a book later, it was when I was taking a break from organizing. Organizing was devastating, but it was work about standing on the shoulders of folks who did the same devastating work as you and using their wins and their losses to inform how you built a thing. I could not write any of these poems without feeling surrounded in the room, because I was an organizer who was broke down, and I was also writing poems that were not like siloed poems. I don’t think that Black people can write siloed poems.

But I definitely was writing about the bigger we. And I wanted to not just speak to Brittany a couple hundred miles away, but also be in a room with you while you were reading. I can’t write a poem that’s naming a thing that I read about before in someone else’s book without acknowledging that I read it in their book. That just feels antithetical to me. When you’re in community with niggas, you name them, you acknowledge them, you immortalize them and their legacy, you pay homage, you say ashe and thank you, and that is craft, that is praxis, that is literally the carving out of the lexicon. If only just for us, I wanted to write a book that was at least attempting to do that work.

Brittany: Oh no, it did that! There’s a section of my crit essay that referenced the audacity of homage, where I look at Mule & Pear by Rachel Eliza Griffiths and the practice of sampling in rap. What you just said sounds so much like the practice of sampling, of recreating in honor of those who came before.

Aurielle: I love that you say sampling too, because I think the first process that I clocked wasn’t slam, it was hip-hop. And in hip-hop it was always ingenious because it was people sampling Duke Ellington and Coltrane and pulling like those first zonophone recordings from the speakeasy, and now there’s a hip-hop head who’s broken it down to just some vocal intonations, and that’s the beat. And sampling is all about connecting a moment to the context.

Brittany: Yes, to what has been! And in the way that I feel like it’s hard to even engage with certain people without being able to go back and respect and honor that history. I’ve been thinking about what it means for writers to acknowledge the importance of saying, “This is who brought me into this room.”

Aurielle: There’s an epigraph in Gumbo Ya Ya from Rhapsody that says, “find the wind, find the air / beneath the kite, that’s the context.” And I love that line from her because you don’t see the air, you just know the kite’s up. You don’t clock it. And sometimes that’s how quiet the nods are, and I think I was just trying to make the quiet nods loud too, because I wanted it to be clear.

There was an after poem in the book that I had to fight with Danez about. They were saying it wasn’t an after poem, but it was for me because I was inspired by the energy of the poem. I thought about that poem that Danez did for weeks! “Psalm in Which I Demand a New Name for My Kindred” is after their poem “Acknowledgments.” And even in that poem, I named Danez as the after, but I literally name all my niggas in the poem.

Brittany: Are there ways that you would say that your writing has changed now that you are not in a space of organizing or necessarily in a space of slam? What has shifted, what hasn’t?

Aurielle: I am giving myself permission to not know. So, I’m still learning the literary lineage beyond the poets a generation behind us. I’m still learning the long arc of Black Poetics and the navigation of a literary space. What I’ve kind of had to do is not allow the fact that I’m green in that literary space to impact how confident and clear I feel in my pen. I really love my voice and where I am now, and I’m trying to allow what I’m learning to positively impact my voice instead of feeling like oh I don’t know about this trochee or I don’t know the greatest hits of Black writers between the ’60s and the ’90s. I’m late to that, for many reasons; one of them being that I didn’t start taking my writing seriously until September 2020 when I won the Cave Canem book prize and thought maybe I can be a writer.

[Since then] I’ve gotten more clear about my voice. I’m clear about what my poetic biases are. I’m clear about what is important to me that might not be important to other poets as far as the rules of English. All I’m trying to do now is gather more tools to learn about a thing so that I can be clear to a reader and a future project and not penalize myself for being late to what I didn’t know before I knew it.

Brittany: That’s part of why I pursued an MFA. It was like I’m doing the work, my homies are doing the work, but there are some spaces where there are things we just don’t have language for. Isn’t that the wildest feeling? To run across a craft term and be like: I do that! I just didn’t know that it had a name.

Aurielle: I been doing that for like five years!!

Brittany: On a similar note, when you did an event on Trans Day of Remembrance, I was so fascinated by what you said about the things that we already know and we’re learning to sharpen them in our writing. What led to the discovery of considering yourself a theorist, and in what ways has that discovery shaped the way that you look at your writing and the writing of other Black poets?

Aurielle: I was reading Dionne Brand’s A Map to the Door of No Return and that book lit me up! I was on fire! Like OMG this book is changing my life. I got to a point in the book where Dionne said something that I had thought before—and I’m not calling myself a genius, I’m not saying I could’ve wrote that book—but Dionne said something very eloquent and in a clear way, and it was something that had crossed my mind before as I was editing Gumbo Ya Ya, and I wanted to follow the path of that thought.

So I went back and started reading Gumbo Ya Ya, and I started to think about what was actually happening. I realized I had attempted to write a book that was physically doing a thing, that was forcing a dynamic between it and the reader or, if you prefer, the reader and me. I wanted to do that because I thought about how flat white poetry is allowed to be and how one dimensional or simple it is allowed to be. And not to say that the writing itself is simple, but the mechanics, the performance of the poems can be simple. And I wanted to name that without being like “white poetics is bullshit,” and that’s theory work. Using form or your own sort of articulation of a thought to reveal something to a reader is theory work. And when you combine it with praxis, how I align the literary space with my politics, my values as an organizer—it’s abolitionist, it’s anti-white supremacy.

I just was like, what is the difference between what’s happening in these eighty some odd pages and theory work, except the difference is you think of the people who are writing theory work as smarter than you. That was my bias. People who do theory work are smart. I used to talk about the book like, “well I ain’t no theorist,” and my friend, Da’Shaun Harrison stopped me one time and was like, “who said!” I consider Da’Shaun a theorist—they clearly wrote fat liberation theory.

(We pause here for a kiki as I show Aurielle my copy of their text, along with Door to No Return on the side of my bed.)

When we were talking, they were like, “you’re carving out a literary fugitivity theory.” The book did—it just didn’t talk about doing it. Here’s what I’ll say—in the spirit of let us all be as audacious and shameless as mediocre white men—if the things you are writing and articulating and chewing on are all you know, it is enough because it is inherently critical and nuanced and multifaceted and complex, because you are a Black person sitting at a multitude of intersections creating work in the world. Gumbo Ya Ya is a book that tries to—from the intersection—reveal the intersection of those who don’t sit there. Right? Because even if there are Black people who are reading the book who identify with the book, they’re being kinda checked because this is a Black queer book, and also even if they are Black queer folks, they might be getting checked because it’s a Black queer book that’s talking about gender freedom and gender expansiveness. The book is sitting at the intersection, naming the intersection, addressing folks outside of it, while trying to wrap its arms around those within like the twelve different intersections that it’s sitting at. And so that is a theoretically complex project.

It’s uncomfortable because of how we are to talk about theory, but theory is abundant, and it’s academia that tries to make it inaccessible. It’s intimidating to be like, I did this thing, I’m so about it, I’m gone tell you what I did, and with an air of importance. Like—yeah! Lol. Theory is doing something with an air of like yeah!

Brittany: It is! I think about how much theory has saved my life . . . In the Wake [:Blackness and Being by Christina Sharpe] saved my life!

(We pause and laugh again as Aurielle reaches behind their desk and pulls out their copy!)

The number of us who need a thing affirmed because we don’t believe it until we see it—that’s its own struggle. You’re so brilliant, and I’m so excited for all the lives your work is going to have, and I’m so excited to be creating in the same time as you.

Aurielle: I can’t wait until this panini press is over, because some of these things I can’t flesh out until I’m in a group of my folks. And we’re writing at midnight. Gumbo Ya Ya was a communal project. I’m working on some essays now that are a communal project. The ideas that are happening in this collection, I really can’t think about until I hop on the phone with my folks.

Brittany: OK! Last question. If someone had to engage with different people or artists to understand your work more fully, which three people would you say they need to engage with?

Aurielle: That’s a great question! Noname—her music and her Twitter. She ain’t on Twitter no more, but go find it in wayback machine. I would say Da’Shaun—same thing, essays and Twitter. And Danez. Of course, Danez.

***

Interviewer Brittany Rodgers is Lead Poetry Editor at REVOLUTE and a MFA candidate at Randolph College’s low-residency program.

AUDIO: AURIELLE MARIE

Notes & Acknowledgements

…

notes & acknowledgments

..well, first I wanna

..recognize th land

..we stand on is stolen

..let it be said here, at least

..that all Black lives matter

..that water is indeed life

..& above all things

..we the people is

..how any patriot

..begins his lie.

I acknowledge th author

tried to craft a project

with faulty agendas

pursued poems as small acts of war

or love letters for a father,

daggers for th 45th president

but those invocations must wait.

I write to you with a soft

hand and gritted teeth

I acknowledge all iterations of Black

rhetorical struggle, myths, and obligations.

all these built with a broken roux or

a liar god. all these, made in earnest attempt at satiety

I acknowledge we are never allowed

any singular monument.

understand, reader

the world is seldom mine

to create; but is indeed, here.

thick with odes & laments & mine &

built by th blood of ebonix, atomized

libraries and anything coaxing our

pleasures erect

Black gxrls— or, as th evening

news has named us, extremists—

are kindred in this anti-making,

already cooking feasts with th dried

skin of nationalists. feasts, our jewels

and old mothers. feasts, sankofa & broth.

we rid this world of all its guns

and elbows, its gum and marrow.

i slurry out a poem from th new world,

stir it into a meal and it’s name is yaya— wild.

welcome. this new world, hallowed by swarms of bees

and language chewed outta jazz.

ours, this world, enraged

over even a splinter

interrupting th palm of our

wildest gxrls

a petit manifesto for grassroots revolutionaries

war strategies for every hood

…………………………..and for Dajerria Becton

there we were—laughing cuz we thought there was nothing left

for them to steal. they came back anyway, to take even the mortar

i guess. the creased sundresses on Lowery Blvd, our bean pies

and turmeric milk. the fish trees opening

their blossomed mouths on MLK, for MLK even

for Morris Brown & the Dome. for the tennis courts

on Washington, for Jazzfest & Auburn. or the tiny dance floor

at Department Store, them virgin mojitos one fine ass DJ snuck us

when we were too young to know better & he, old enough to notice

someone stole our grandmothers’ laundry carts & charged us

to rent them back by the hour. & every other hour they bombed

another neighborhood. gave it leftover letters from places they ruined: SoMad, WeHo, WestMar

they came for the AUC, unearthed bricks lining our streets like copper bullets

they came to drive the corner preachers over county lines. the prostitutes

too & when our daughters left the house, they returned to us soaking. wet

rows of hair missing from their young scalps. backs purpled by the knees of policemen.

not long before now, what little they allowed us learn,

we learned. whatever corner they gave us for us, we kept for us

stayed the borders they drew round our toddles & swaddled our bodies in red

ink. now what? they came bringing shiplap and measuring tape

they filled our mouths with salt, our pools with teeth

they came to turn our wounds into deeds, our rubble to profit

and they did.

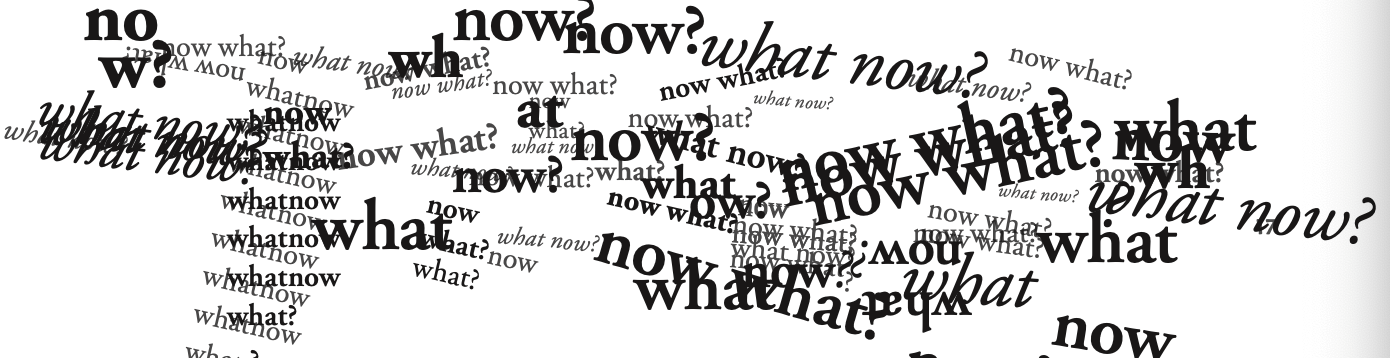

& now what? now what? now what? now what?

now what? now what? now, what? what now? what now? what now?

the night after our evictions we were no more

the night after our evictions we were no more

than petty cash offers, liens, dethroned ghetto kings

our delicate empires gutted by quiet legislation

a condition of battle, they called it, precautionary measures

we do what little we have left to do: slit the braids from our scalps

twenty inches at a time, whittle our nails into daggers, and march. we lure policemen

into narrow alleys and from behind them, rope hair

from our fists unto their necks. a condition of battle. precautionary measures.

from out our homes, flood their pleading faces. gentrifiers

bartering for mercy with china from our mothers’ closets

but we war blood now, cashed our mortgages in for machetes and kanekalon

our braid lynch cords slip into loops around their necks. held taut for small eternities

& then, finally let slack. over & a condition of battle over & precautionary measures & over & a condition of over &

for our niggas, our mothers, our hood

we sang

for our daughters

our daughters

our daughters.

transhistorical for the men we love

iv.

he knew a few cats frm back when snow hit them bluffs

hard enuf to splinter concrete like bone

he dont talk bout them years but i dun seen scars

runnin ‘cross his faces like old haints

them wounds. everytime a car engine cough into th mornin

or a mother call for her children at dusk

somethin darken his whole body up into fury

& ther aint no porch blu enuf to quiet them ghosts

ii.

long ‘fo poverty swallow up tha southwest side

we knew kings on every corner who lit th sidewalk

wit urine & magic, or bathed inna hydrant’s summer song

they grac’d each juke joint door like cathedrals wit pipe glass

& th nights was all hymnals at th neck ov a bottle

back home they aint no such thing as a ghetto or domestic violence.

All th sons of men were heirs of hood glory but us women inherit

always th bruises & bills. this here was th world b’tween my father & i

iii.

this wound my daddy survive. i dig in th bloodmess ova & ova & call

it a poem. my daddy got a heifer fo’ a daughter & love me

like a wound— medicinal. i airs his shit into a cold metal lattice

every thursday. kill his ego so quick, these fast lips itchin fo’ bruise. he dun

learned to withhold. i refuse to play wife inna home wit no heat

& he leave me to ruin now, ‘stead uh ballin his fists. aint that growths otha name?

eldest born of th red mud, miridional & audacious, I’m my father’s daughter—

beveled by th third zone of his rage and th good, prodigious wild

i.

of course i wanted him to love me as if i was a boy-child. of course i wanted to earn

a man’s birthright: respect by some otha name, th retiring of his fists against my side

i got none of these. i am only a girl who knew her mouth cud be a small fist upside

her daddy neck & if that wuz all the power i had, i shole wan’t finna discard

it inna name of principle. myself i wuz sittin tall when men walked my way— expensive

and feral. if every man was a father, then i became the ruin of patralineage, the death

of my daddy by my hands, my thighs, my defiance. i wish i cud tell u the end was beautiful