| Microreviews |

William Woolfitt. The Night the Rain Had Nowhere to Go. Belle Point Press, 2024, 76 pages.

Reviewed by Lesley Wheeler

Lists are powerful instruments for poetry: Naming builds worlds, even when items in the catalogue are lost or endangered. The Night the Rain Had Nowhere to Go, William Woolfitt’s beautiful fourth collection, brims with lists. The abecedarian “West Virginia in the Later Anthropocene” presents a litany of rapid and gradual catastrophes, including flooded cities, the emerald ash borer, and “the slow green fire of / kudzu” (4). Other list-poems collage quotes, identify foraged foods, and bear witness to Appalachian people and places sickened by coal mining and its legacies.

The primary way Woolfitt subverts ongoing disaster, though, is by creating playlists all through the book, most resonantly in an intermittent series labeled “Track One: The Wreck on the C. & O.” through “Track Nine: In the Pines.” Each is cued to a gospel, blues, or folk song that speaks to suffering and persistence. This silent mixtape evidences the book’s scholarly underpinning—this is a deeply researched collection—as well as Woolfitt’s commitment to remembering decades of racial violence in Appalachia’s diverse communities. Many of the songs he echoes emerge from Black and Native traditions, such as “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot,” which we probably owe to Afro-Indigenous composers Wallace and Minerva Willis. Woolfitt honors and grieves loss without whitewashing West Virginia and Tennessee. Here are mountain sweeps and bodies “mined and stripped” (13); Black and Cherokee people conscripted to dig coal; poisoned creeks and looted graves.

Music also testifies in a ringing way to Woolfitt’s love of Appalachia and his sense of its continuing abundance. In the peaks and hollows he evokes—and everywhere else—art, landscape, and living creatures are interdependent. That’s a crucial tune to plant in our minds. May it catch in more of us.

____

Lesley Wheeler, Poetry Editor of Shenandoah, is the author of six poetry collections, including Mycocosmic, forthcoming from Tupelo Press in March 2025, and The State She’s In. Her other books include the hybrid memoir Poetry’s Possible Worlds and the novel Unbecoming. Her poems and essays have appeared in Poets & Writers, Pleiades, Poetry, Ecotone, and The Massachusetts Review.

Jenny George. After Image. Copper Canyon Press, 2024, 73 pages.

Reviewed by Rene Mullen

In After Image, Jenny George never allows readers to stew with her in shared grief. Instead we join her in a vignette tapestry of moments—subtly haunting moments of quietude. Quiet, short, unassuming moments where the narrator is reminded of a passed-on lover coupled with moments of sadness because of the loss—and there is a difference. We are given seemingly meditative ordinary incidents contemplating the complexity of nature and human existence after we lose someone dear to us. The collection becomes a “carrier bag” of collected tchotchke memories in the way that Ursula K. Le Guin described. Though this is not fiction, the story etches significance for readers rather than the sensation itself of grief and loss.

The collection’s title refers to the illusion we’ve all experienced when an image remains after the object or original image has gone. The lover’s after-image remains with the narrator. “She died. It floats on my vision like a burn,” as a shadow scar in the mind’s eye and so much of what the narrator experiences moving forward. As George writes, “I find death where it is: / simultaneous with life,” where George keeps readers—in the present moment with memory, grief, love, life, and death all at once. Perhaps this is the beauty by which George leads readers with an empathetic hand through the reality that is life: death and connection, meetings and partings.

After Image is part eulogy to a lover lost, part story of the imprint left behind, speaking to the remnants of love with nowhere to go. Often, we write of loss and grief; it’s one of our oldest, most complicated life events. But seldom does one honor the honest suffering while landing in the realm of gratitude for the imprint.

____

Rene Mullen’s work can be found in The Santa Fe Literary Review, Blue Collar Review, and Poets.org. Rene is the winner of the 2023 Charles and Fanny Fay Wood Poetry Prize. Rene has been on multiple poetry slam teams, on regional stages, and holds an MA in Political Science from the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee and an MFA from Randolph College. Born and raised in the village of Rogers, Connecticut, Rene calls the Southwest home.

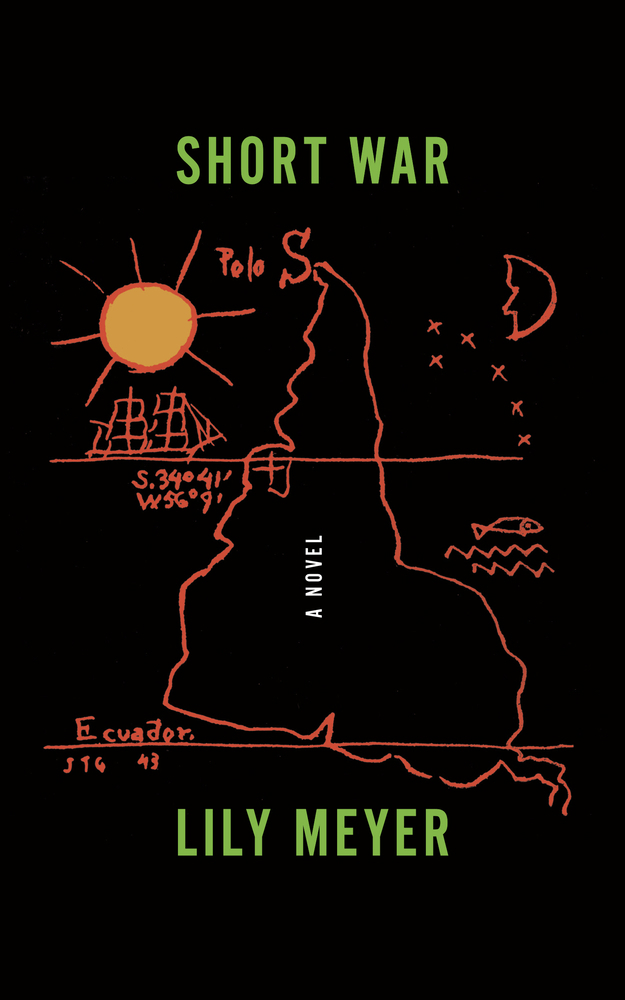

Lily Meyer. Short War. A Strange Object, 2024, 270 pages.

Reviewed by Jennifer Kane

The opening pages of Lily Meyer’s reckoning novel Short War exude the cultural liminality and adolescent cool of being an American teenager at a party in Latin America. This reads like lived experience, and Meyer notes in the acknowledgments that her “obsession with U.S. intervention in Chile” started when she was a sixteen-year-old exchange student in Quillota.

As someone who was also a white American exchange student in South America, I’m tempted to say it takes one to know one. However, Meyer turns any intimation of coy solidarity from readers on its head. Across three linked narratives—crisis, interpretation, and decision—Short War explores the multi-generational fallout of the 1973 military overthrow of Chile’s democratically elected government and grapples with questions of moral debts and complicity.

As with many reckonings, the debts in question are owed by the privileged. Gabriel Lazris is a sixteen-year-old American Jew living in Santiago, Chile who attends a fancy Catholic boys’ school and suspects his conservative journalist father is engaged in CIA activities. When the coup occurs, the Lazris family flees for the U.S., and Gabriel leaves behind his Chilean girlfriend and best friends.

Decades later, Gabriel’s adult daughter Nina is an American graduate student comfortably adrift in Buenos Aires and the first of the Lazris family to return to South America after the coup. A romantic entanglement with a local academic leads to the discovery of a book that reveals a family secret, driving “selfish, unserious” Nina in search of answers.

Through the experiences of the American Lazris family and their Chilean loved ones, Meyer deftly illustrates how U.S. involvement in Latin America plays out on a human scale. She also wades into the fraught waters of what the privileged owe. When Nina learns new details about her family and the coup, she is livid with her father. “All his talk of privilege, all his efforts to teach her to use hers wisely and warily, and what had he done with his?” Short War prompts readers to consider the same question about privilege—what will we do with ours?

____

Jennifer Kane is a writer based in the DC Area. She holds an MFA from Randolph College, where she was a Blackburn Fellow and Lead Fiction Editor for Volume .005 of Revolute. She is currently working on a short story collection and a novel about field biologists in Panama.